Abstract

In early eighteenth century New York, Haudenosaunee, Dutch, English, other European settlers, and enslaved African people worshipped together at Queen Anne's Chapel in Fort Hunter. The 1711 construction of this fort and the chapel within it was intended to tie together the many contentious settler ethnic groups and neighboring Mohawks in a single British and Anglican community. This article uses social network analysis to examine ties created between congregants by Anglican baptism. The relations documented by these baptisms made visible the ways in which ethnic and racial boundaries were created, maintained, and occasionally bridged. In the network created by baptismal connections between parents, children, and godparents, women's connections functioned as the primary social glue connecting the disparate ethnic groups within the congregation. Haudenosaunee parents used Anglican baptism to reinforce matrilineal clan ties, while Indigenous and settler women across the congregation were the primary connectors between otherwise separated ethnic groups. Only one Dutch female trade connected the Indigenous and settler portions of the congregation, challenging scholarly focus on male diplomats as the primary intercultural mediators in early New York. Both settler and Indigenous women navigated cross-cultural contact differently than their male counterparts, and those patterns of contact and mediation have not always been archivally visible because of their gendered differences.

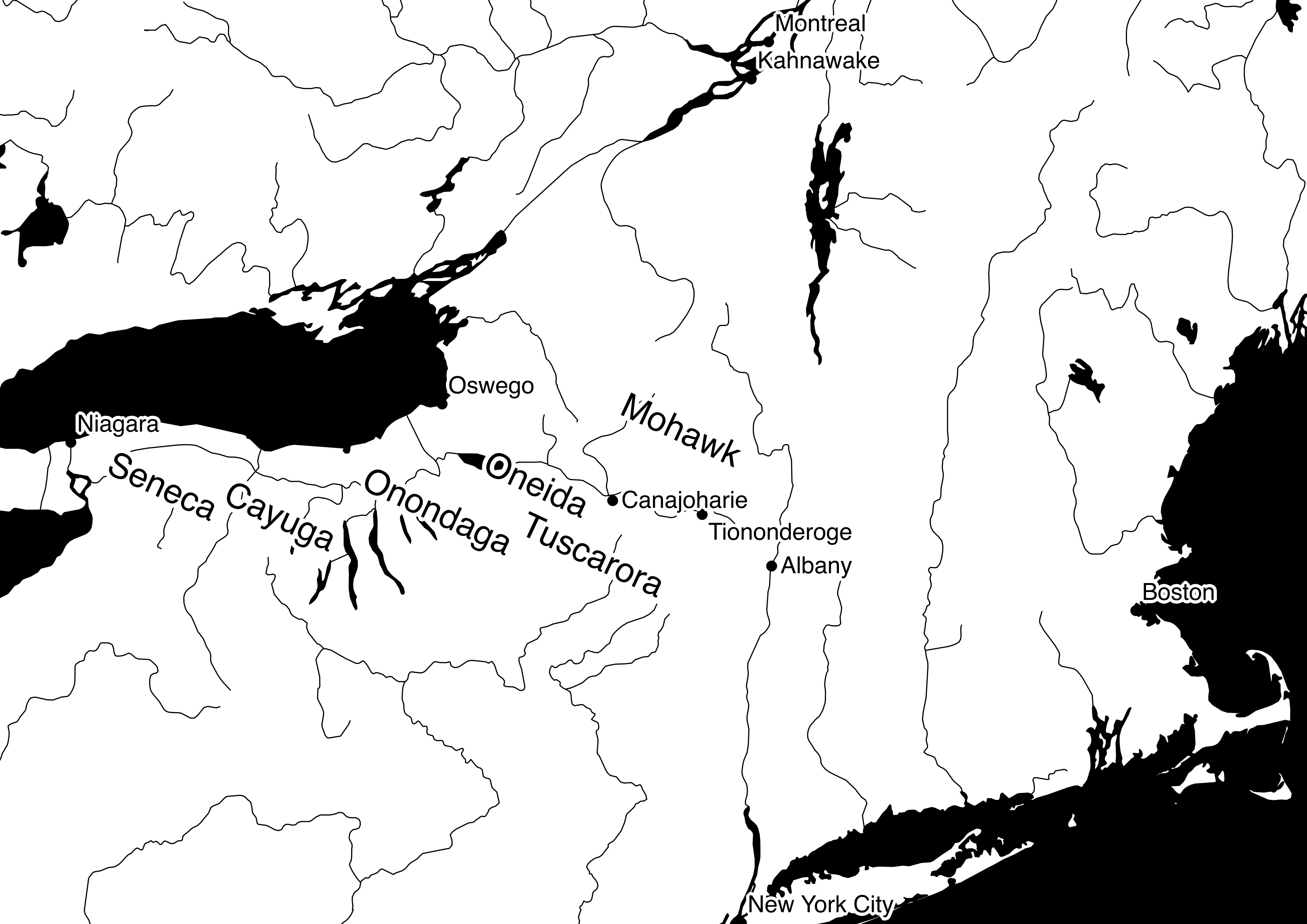

The 1711 construction of Queen Anne's Chapel in Fort Hunter was intended to serve many goals for the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and New York colonial leaders who requested it, the British metropolitan officials who funded it, and the Haudenosaunee and settler congregants who attended it. Peter Schuyler, mayor of Albany, and the "Four Indian Kings" (actually three young Mohawks and a Mahican without real political authority) traveled to London in 1710 to more firmly tie British imperial interests to the defense of New York and Native communities against French incursion.On the Four Indian Kings' lack of authority and the way the envoy entered the British imperial imagination, see Hinderaker, "The "Four Indian Kings"; Richter, The Ordeal of the Longhouse, 229-230 and 368n29; Bond, Queen Anne's American Kings; Stevens, "Tomahawk"full note Queen Anne funded the construction of a fort in Mohawk territory and a chapel within its walls, hoping to build on previously spotty Dutch and Anglican conversion efforts among the Mohawk and prevent further Catholic conversions by French Jesuits.On previous Dutch and English mission efforts in the Mohawk Valley, see William B. Hart, "Mohawk Schoolmasters and Catechists in Mid-Eighteenth-Century Iroquoia: An Experiment in Fostering Literacy and Religious Change," in Edward G. Gray and Norman Fiering, eds., The Language Encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800, (New York: Berghahn Books, 2000), 230-57; William B. Hart, "For the Good of Our Souls: Mohawk Authority, Accommodation, and Resistance to Protestant Evangelism, 1700-1780" (Ph.D. diss., Brown University, 1998), 213-34; William Fenton, The Great Law and the Longhouse: A Political History of the Iroquois Confederacy (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 248-60, 364, 367; Daniel K. Richter, "'Some of Them... Would Always Have a Minister with Them': Mohawk Protestantism, 1683-1719," American Indian Quarterly 16, no. 4 (1992): 471-84, https://doi.org/10.2307/1185293; Daniel R. Mandell, "'Turned Their Minds to Religion': Oquaga and the First Iroquois Church, 1748-1776," Early American Studies 11, no. 2 (2013): 211-42, https://doi.org/10.1353/eam.2013.0017; Rowan Strong, "A Vision of an Anglican Imperialism: The Annual Sermons of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts," Journal of Religious History 30, no. 2 (2006): 175-98. On previous Catholic missions to the Mohawk, see Hart, "For the Good of Our Souls", 36; Fenton, Great Law, 248-60, 364, 367; James Axtell, The Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 43-126; Alan Greer, Mohawk Saint: Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).full note For the Anglican Mohawks at Tiononderoge and the nearby Dutch, English, Scots, Irish and Palatine German settlers and enslaved Africans who attended service and baptized their children at Queen Anne's Chapel, the spiritual community at Fort Hunter both bound their communities together and reinforced ethnic and racial distinctions within the congregation.

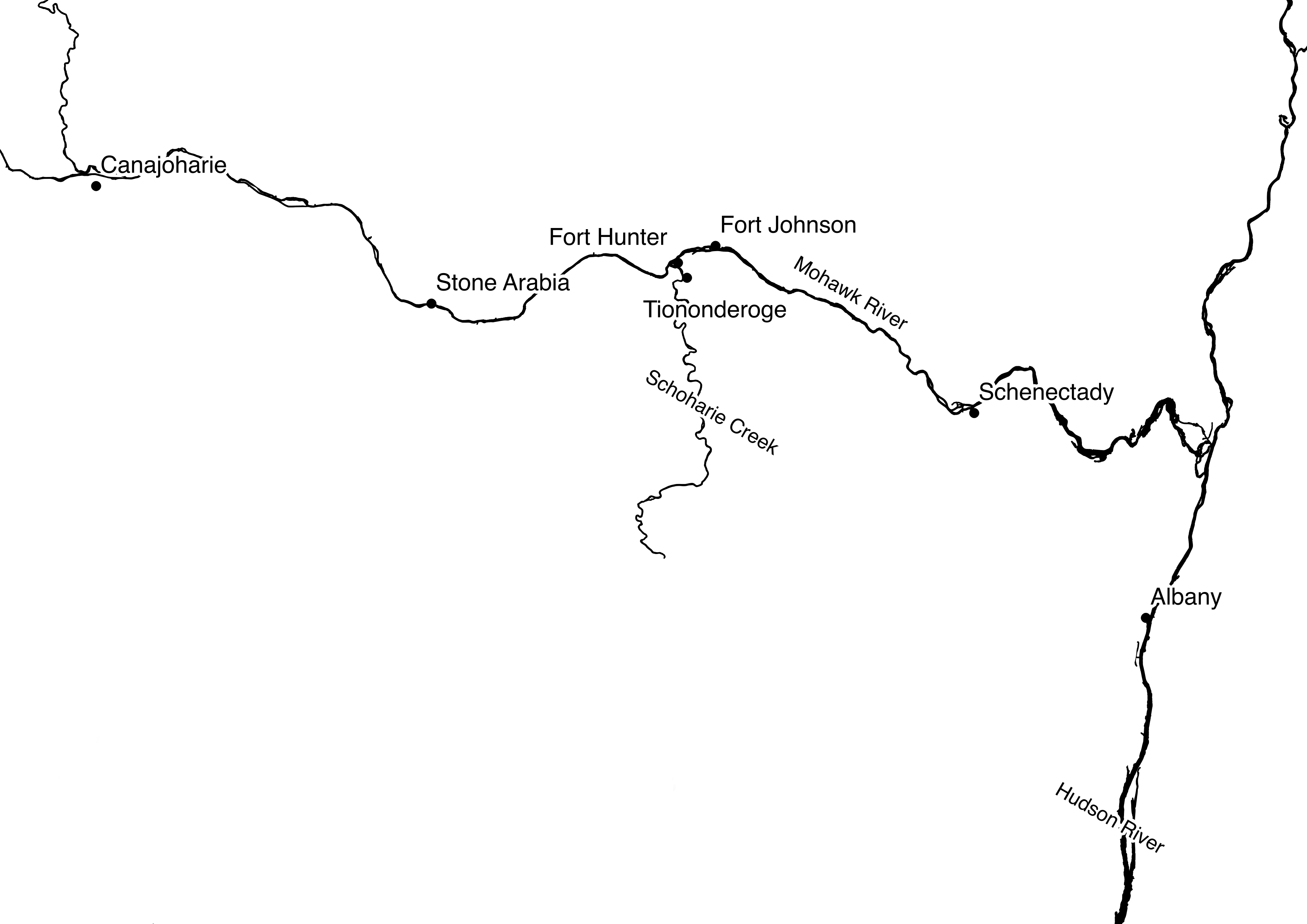

The disparate ethnic communities within the Fort Hunter congregation practiced baptism and sponsorship in different ways. The Mohawk community of Tiononderoge, where most of the Haudenosaunee Fort Hunter congregants lived, had a long history of mixed material culture in which European goods were used and reworked to fit Indigenous contexts, as well as a hybrid practice of Christianity which blended Indigenous, Catholic, and Protestant elements.On Mohawk mixed material culture, see Kevin Moody and Charles L. Fisher, "Archaeological Evidence of the Colonial Occupation at Schoharie Crossing State Historic Site, Montgomery County, New York," The Bulletin: Journal of the New York State Archaeological Association, No. 99 (1989), 8; Gail D. MacLeitch, Imperial Entanglements: Iroquois Change and Persistence on the Frontiers of Empire. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 175-210; David Preston, The Texture of Contact: European and Indian Settler Communities on the Frontiers of Iroquoia, 1667-1783 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 178-215; Kurt Jordan, The Seneca Restoration 1715-1754: An Iroquis Local Political Economy (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008), 264 and 342; Carolyn Shine, "Scalping Knives and Silk Stockings: Clothing the Frontier, 1780-1795," Dress, 14 (1988), 39-47; Timothy J. Shannon, "Dressing for Success on the Mohawk Frontier: Hendrick, William Johnson, and the Indian Fashion," The William and Mary Quarterly 53, no. 1 (1996): 13-42. See also the purchases of Tiononderoge Mohawks in Jelles Fonda, "Account Book," 1768-1775. BV Indian Trader, New York Historical Society, New York, NY and Jelles Fonda, "Indian Book for Jelles Fonda at Cachsewago," 1758-1763. MS651-647, Old Fort Johnson, Fort Johnson, NY. On hybrid Mohawk spiritual practice, see Richter "Some of Them" and Mandell, "Turned Their Minds to Religion."full note As a result of a long-disputed land purchase, Dutch and English residents of Albany settled near Fort Hunter and brought enslaved Africans with them.Barbara J. Sivertsen, Turtles, Wolves, and Bears: A Mohawk Family History (Westminster, MD.: Heritage Books, 2006) 42-47; Oliver Rink, "The People of New Netherland: Notes on Non-English Immigration to New York in the Seventeenth Century," New York History 62 (1981):5-42, and David S. Cohn, "How Dutch Were the Dutch of New Netherland?" New York History 62 (1981):43-60.full note In addition to these groups, in 1710 New York governor Robert Hunter sponsored the settlement of thousands of Palatine German refugees in the pine barrens of the Mohawk and Hudson Valleys in a scheme to make naval stores for the Royal Navy and provide refuge for Protestants displaced by war in Europe."Governor Hunter to the Lords of Trade," 1715, in John Romeyn Brodhead, Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York (Weed, Parsons, Printers, 1861), 5:460; A. G. Roeber, Palatines, Liberty, and Property: German Lutherans in Colonial British America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 12-16 and 21-24; Lawrence Leder, "Military Victualling in Colonial New York," in Business Enterprise in Early New York, ed. Joseph Frese, SJ, and Jacob Judd (Tarrytown NY, 1979) 16-54; Michael G Kammen, Colonial New York (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 177-179; Sivertsen, 72-74; Philip Otterness, Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2006), 92-96, 99-102, 119-125, 128-131; MacLeitch, 93-94; Sung Bok Kim, "A New Look at the Great Landlords of Eighteenth-Century New York," The William and Mary Quarterly, 27, No 4 (October 1970), 581-614; Robert Kuhn McGregor, "Cultural Adaptation in Colonial New York: The Palatine Germans of the Mohawk Valley" New York History, 69, No. 1 (1988), 21.full note When the pitch scheme turned sour, delegations of Palatines established friendly relations with Schoharie Valley Mohawks and settled instead on fertile farmland along Schoharie Creek.Colonel Guy Johnson, "A General Review of the Northern Confederacy and the Department for Indian Affairs," October 3, 1776, photostat 280, box 2, British Headquarters Papers New York Public Library; Barbara Graymont, The Iroquois in the American Revolution (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1972), 5-6, 14, 55; Eric Hinderaker, Elusive Empires : Constructing Colonialism in the Ohio Valley, 1673-1800 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 10; Alan Taylor, The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 4; Francis Jennings, "The Indians' Revolution," in The American Revolution: Explorations in the History of American Radicalism, ed. Alfred F. Young (Dekalb, IL, 1976), 324.full note This angered Dutch and English elites in Albany and Governor Hunter, all of whom had begun speculating on the land along Schoharie Creek despite Mohawk objections.James Paxton, Joseph Brant and His World, (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 2008), 12-13.full note After 1718, Ulster Scots and Protestant Irish filtered into the area as well, including William Johnson, who arrived in 1738 to administer land his uncle had bought in the area.Kammen, 178-179; Henry Jones Ford, The Scotch-Irish in America (Princeton University Press, 1915), 249-259; Fintan O'Toole, White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005), 37; Patricia U. Bonomi, Factious People: Politics and Society in Colonial New York, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1971), chapters 1 and 2 passim; 4-6o; David L. Preston, "George Klock, the Canajoharie Mohawks, and the Good Ship Sir William Johnson: Land, Legitimacy, and Community in the Eighteenth-Century Mohawk Valley," New York History 86, no. 4 (Fall 2005).full note Henry Barclay noted that Johnson, Johnson's cousin Mick Tyrell, and the twelve Irish Protestants who accompanied them were "very honest, sober, industrious, and religious" though fractious.Quoted in O'Toole, 41.full note In addition, some Mahicans moved west from their territories east of the Hudson River to seek agricultural work with European landowners or as indentured servants.On the impact of colonialism, debt, and indentured servitude among northeastern Algonquian groups, see Robert S. Grumet, The Munsee Indians: A History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009); Paul Otto, The Dutch-Munsee Encounter in America: The Struggle for Sovereignty in the Hudson Valley (New York: Berghahn Books, 2006); Daniel R. Mandell, Behind the Frontier: Indians in Eighteenth-Century Eastern Massachusetts (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996); David J. Silverman, "The Impact of Indentured Servitude on the Society and Culture of Southern New England Indians, 1680-1810," The New England Quarterly. 74, no. 4 (2001): 622.full note

In this mixed landscape, people from two Native nations with very different relations to settler communities, European ethnic groups at odds with one another, and enslaved Africans all attended church and had their children baptized at Queen Anne's Chapel. The relations documented by these baptisms made visible the ways in which ethnic and racial boundaries were created, maintained, and occasionally bridged. In the network created by baptismal connections between parents, children, and godparents, women's connections functioned as the primary social glue connecting the disparate ethnic groups within the congregation. One of the few experiences most women shared in common across race and ethnicity was the use of baptism to connect otherwise distinct ethnic and racial communities. In the most prominent example within the Fort Hunter congregation, Anna Peek, an illiterate Dutch woman trader and tavern owner, functioned as the sole intercultural go-between who connected the otherwise separate Indigenous and settler portions of the congregation. In eighteenth century New York, male go-betweens signaled their status as mediators with performatively mixed clothing in diplomatic spaces.On male intercultural mediators, see Daniel K Richter, "Cultural Brokers and Intercultural Politics: New York-Iroquois Relations, 1664-1701," The Journal of American History 75, no. 1 (1988): 40-67; Richter, "Some of Them": 471-84; Richter, Ordeal; Edward Countryman, "Toward a Different Iroquois History," The William and Mary Quarterly 69, no. 2 https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.69.2.0347 (2012): 347-60; Mandell, "'Turned Their Minds to Religion'": 211-42; Eric Hinderaker, "Translation and Cultural Brokerage," in Philip J. Deloria and Neal Salisbury, eds., A Companion to American Indian History (Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004), 357-75; Shannon, "Dressing for Success": 13-42.full note Unlike these male mediators, Peek appears in very few other archival sources and her role as intercultural go-between at Fort Hunter was a result of her prosaic daily interactions with her Indigenous neighbors. Her prominence connecting the otherwise separate Haudenosaunee and settler portions of the Fort Hunter congregation suggests that women navigated intercultural contact differently than did men in the same community, within the social and domestic space of daily contacts built up over time to fictive kinship, rather than the performative and temporary space of diplomatic meetings.

Within the otherwise separate settler and Indigenous portions of the congregation, women used baptism to cement ties between ethnic and clan subcommunities. In addition to Peek, settler women who married men of different ethnicities used baptism to maintain ties to their natal ethnic communities, while Haudenosaunee women used Anglican baptism to reinforce matrilineal clan connections. These parallel uses of baptism fit the shared religious rite to each group's social and cultural needs even as the act of baptism made visible the boundaries between ethnic and racial groups within the congregation. Haudenosaunee women in this community did not intermarry with settler men.Susan Sleeper-Smith, ed., Rethinking the Fur Trade: Cultures of Exchange in an Atlantic World (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009); Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indigenous Prosperity and American Conquest: Indian Women of the Ohio River Valley, 1690-1792, (Chapel Hill: Omohundro Institute and University of North Carolina Press, 2018); Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes, (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001); Michele Mitchell, "Turns of the Kaleidoscope: Race, Ethnicity, and Analytical Patterns in American Women's and Gender History." Journal of Women's History 25:4 (2013): 46-73; Robert Michael Morrissey, "Kaskaskia Social Network: Kinship and Assimilation in the French-Illinois Borderlands, 1695-1735," William and Mary Quarterly 70, no. 1 (2013): 103-46. For an examination of the importance of nation, ethnicity, and Indigenous political power to Native women's intermarriage, see Kathleen DuVal, "Indian Intermarriage and Metissage in Colonial Louisiana," The William and Mary Quarterly 65:2, 2008: 267-304. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25096786. For one case of a female diplomatic broker in eighteenth century Iroquoia, see Jon Parmenter, "Isabel Montour: Cultural Broker on the Frontiers of New York and Pennsylvania," in The Human Tradition in Colonial America, ed. Ian Kenneth Steele and Nancy L Rhoden (Wilmington, Del.: SR Books/Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1999), 141-59; and Alison Duncan Hirsch, "'The Celebrated Madame Montour': Interpretess across Early American Frontiers," Explorations in Early American Culture 4 (2000): 81-112.full note The cross-cultural ties they created were selective ones of godparentage, which symbolically positioned Indigenous and settler godparents as brothers and sisters to each other and as aunts and uncles to the baptized child. The relationships of aunt and uncle, especially maternal ones, are among the most culturally important familial relationships for Haudenosaunee families; in eighteenth century diplomacy, the metaphor of uncle and nephew denoted obligations of education, protection, and respect.For discussion of familial diplomatic metaphors in the eigtheenth century, see Nancy Shoemaker, "An Alliance between Men: Gender Metaphors in Eighteenth-Century American Indian Diplomacy East of the Mississippi," Ethnohistory 46, no. 2 (1999): 239-63; Erik R. Seeman, "Uncovering Hudson Valley Indian History." Reviews in American History 41:2 (2013): 191-196; Brenda Macdougall. "Speaking of Metis: Reading Family Life into Colonial Records." Ethnohistory 61:1 (Winter 2014), 31-32; Gunlog Fur, A Nation Of Women: Gender And Colonial Encounters Among The Delaware Indians. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012; Jane T. Merritt, "Cultural Encounters along a Gender Frontier: Mahican, Delaware, and German Women in Eighteenth-Century Pennsylvania," Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 67, no. 4 (2000): 502-31; Jane T. Merritt, At the Crossroads: Indians and Empires on a Mid-Atlantic Frontier (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 51-59.full note By integrating a limited number of settler neighbors through godparentage as adoptive aunts and uncles, Haudenosaunee parents selectively deployed a Christian ritual to accomplish a culturally Haudenosaunee goal.

This project uses digital social network analysis to examine the baptism register kept by the Anglican minister Henry Barclay at Queen Anne's Chapel between 1735 and 1745. As a snapshot of this mixed-ethnicity community, social network analysis of the baptism register offers a window on both the social connections among the many ethnic groups living in early New York, as well as one view of what settlers like Barclay were able to see of their Indigenous neighbors' social connections. The network examined here is solely reconstructed from what Barclay recorded in the Fort Hunter register analyze not only who was connected to who in this congregation, but also to analyze who it was visible to.Digital humanities methods have been critiqued for reifying a focus on "big data," including large bodies of print sources that are easily processed by computer and by definition outside the capacity of any one scholar to read completely. For discussion of these critiques, see Sharon Block, "#DigEarlyAm: Reflections on Digital Humanities and Early American Studies," The William and Mary Quarterly 76, no. 4 (November 2019): 641; Lee Skallerup Bessette, "W(h)ither DH? New Tensions, Directions, and Evolutions in the Digital Humanities," in Disrupting the Digital Humanities, ed. Kim and Stommel ([Santa Barbara, Calif.], 2018): 419-53; Jo Guldi and David Armitage, The History Manifesto, vol. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781139923880 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781139923880. Recent digital history work, including work in early American history, has illustrated the possibilities of DH for fine-grained analysis of both big and tiny data. For examples of recent scholarship, see Lara Putnam, "The Transnational and the Text-Searchable: Digitized Sources and the Shadows They CastThe Transnational and the Text-Searchable," The American Historical Review 121, no. 2 (April 1, 2016): 377-402, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/121.2.377; Julia Laite, "The Emmet's Inch: Small History in a Digital Age," Journal of Social History (February 2019): 1-27; Morrissey, "Kaskaskia Social Network": 103-46, https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.70.1.0103; Maeve Kane, "For Wagrassero's Wife's Son: Colonialism and the Structure of Indigenous Women's Social Connections, 1690-1730," Journal of Early American History 7, no. 2 (July 21, 2017): 89-114, https://doi.org/10.1163/18770703-00702002; Sharon Block, Colonial Complexions: Race and Bodies in Eighteenth-Century America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018).full note Digital humanities is one technique among many now available to scholars, like ethnohistory and material culture studies, that enables "multivocal" histories to more fully examine Indigenous-settler relations.Sharon M. Leon, "Silence and Blindness: Newman's Digitally Enhanced Imaginary," The William and Mary Quarterly 76, no. 1 (February 5, 2019): 19-24; Edward L. Ayers, "Does Digital Scholarship Have a Future?" EDUCAUSE Review 48, no. 4 (July/August 2013), https://er.educause.edu/articles/2013/8/does-digital-scholarship-have-a-futurefull note

This multivocality is especially important in Indigenous histories where archival documentation is often sketchy, skewed, or entirely absent.On archival silencing in traditional and digital history, see Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995); Kane, "For Wagrassero's Wife's Son": 89-114; Morrissey, "Kaskaskia Social Network" 103-46; Laura Klein, "The Image of Absence: Archival Silence, Data Visualization, and James Hemings," American Literature 85, no. 4 (2013): 661-88. For an entangled indigenous and settler network which does attempt to reconstruct the totality of all social ties, see Morrissey, "Kaskaskia Social Network" and Robert Michael Morrissey, "Archives of Connection." Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 48, no. 2 (2015): 67-79.full note As a document, the Fort Hunter baptism register is profoundly colonial. After the 1711 construction of Queen Anne's Chapel, services were held at Fort Hunter sporadically for the next twenty years by ministers based in Schenectady and Albany, who recorded equally sporadic baptisms and marriages among the nearby Indigenous and settler residents.On Indian conversion in early New York, see Jean Fittz Hankins, "Bringing the Good News: Protestant Missionaries to the Indians of New England and New York" (Ph.D. diss., University of Connecticut, 1993); John Frederick Woolverton, Colonial Anglicanism in North America (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1984) 103; Allan Greer, "Conversion and Identity," in Conversion: Old Worlds and New Kenneth Mills and Anthony Grafton, eds., (Rochester, N.Y.: University of Rochester Press, 2003); Neal Salisbury, "Embracing Ambiguity: Native Peoples and Christianity in Seventeenth-Century North America," Ethnohistory 50 (2003) 247-59; Edward E. Andrews, Native Apostles (Harvard University Press, 2013); Linford D. Fisher, The Indian Great Awakening: Religion and the Shaping of Native Cultures in Early America, (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014).full note Henry Barclay, the son of one of these ministers, was appointed by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel as catechist to Fort Hunter in 1735 and began keeping a regular "Register of Baptisms, Marriages, Communicants and Funerals at Fort Hunter" in which he recorded the names of children baptized, their parents, godparents, witnesses and sponsors.Henry Barclay, Register of Baptisms, Marriages, Communicants and Funerals at Fort Hunter, 1734. New-York Historical Society, BV Barclay, http://nyheritage.nnyln.org/digital/collection/p16124coll1/id/45331/. For further discussion of Barclay's mission work, see Sivertsen, 125; Samuel Hopkins, Historical Memoirs Relating to the Housatonic Indians (New York: W. Abbatt, 1911), 27; John Wolfe Lydekker, The Faithful Mohawks. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 53-54. On early Anglican practices of register keeping, see Shirley Spragge, "'One Parchment Book at the Charge of the Parish . . . ': A Sample of Anglican Record Keeping," Archivaria 30 (Summer 1990): 55-63.full note Barclay was employed by the SPG to missionize both the Mohawk and unchurched Dutch, German, and English settlers near Fort Hunter.On the work of the S.P.G. in New York to convert non-English settler congregants see John Calam, Parsons and Pedagogues: The S.P.G. Adventure in American Education (New York, 1971); Carson I. A. Ritchie, Frontier Parish: An Account of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel and the Anglican Church in America, Drawn from the Records of the Bishop of London (Rutherford [N.J.], 1976); Joyce D. Goodfriend, "The Social Dimensions of Congregational Life in Colonial New York City," The William and Mary Quarterly 46, no. 2 (1989): 266 https://doi.org/10.2307/1920254full note As a product of settler colonialism, Barclay's register represented an attempt by the Church of England to convert, integrate, and ultimately replace the Mohawk community surrounding Fort Hunter with Anglican settlers.For recent discussion of the utility of settler colonialism as a concept in the early history of eastern North America, see Daniel K. Richter, "His Own, Their Own: Settler Colonialism, Native Peoples, and Imperial Balances of Power in Eastern North America, 1660-1715," in The World of Colonial America: An Atlantic Handbook, ed. Ignacio Gallup-Diaz (New York, 2017), 209-33; Jeffrey Ostler, "Locating Settler Colonialism in Early American History," The William and Mary Quarterly 76, no. 3 (July 31, 2019): 449; Nancy Shoemaker, "A Typology of Colonialism," Perspectives on History 53, no. 7 (October 2015), https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/october-2015/a-typology-of-colonialism.full note Barclay recorded baptisms and occasional marriages in patrilineal, patriarchal form with primacy given to the father's name, thus inscribing Indigenous relations in Anglican forms. As one of the structures of settler colonialism, mission efforts like Barclay's helped lay the foundations for settler claims to the Mohawk Valley and the violent dispossession of Mohawk families within a generation after the outbreak of the American Revolution.For Mohawk losses during the American Revolution, see Preston, The Texture of Contact; Maeve Kane, "She Did Not Open Her Mouth Further: Haudenosaunee Women as Military and Political Targets During and After the American Revolution.," in Women in the American Revolution: Gender, Politics, and the Domestic World, ed. Barbara Oberg (University of Virginia Press, 2019). On settler colonialism as a structure, see Patrick Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native," Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 388; Patrick Wolfe, "Recuperating Binarism: A Heretical Introduction," Settler Colonial Studies 3, nos. 3-4 (2013): 257-79; Ostler, 450.full note

At the time of Barclay's mission efforts, settler colonialism in the Mohawk Valley and indeed much of early New York was incomplete. Mohawks adopted Anglican practice, but they did so in ways that fit their own cultural needs despite the intent of Barclay and English settlers like him. A careful reading of godparentage connections in both the settler and Haudenosaunee portions of the congregation reveal that Mohawk Anglicans at Fort Hunter used Christian rites like baptism to reinforce rather than replace Indigenous kinship structures.On Indigenous survivance and settler colonialism, see J. Kehaulani Kauanui, "'A Structure, Not an Event': Settler Colonialism and Enduring Indigeneity," Lateral 5, no. 1 (Spring 2016), https://doi.org/10.25158/L5.1.7; Aimee Carrillo Rowe and Eve Tuck, "Settler Colonialism and Cultural Studies: Ongoing Settlement, Cultural Production, and Resistance," Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies 17, no. 1 (February 2017): 3-13full note As a period of intense social, economic, and political change for Haudenosaunee and settler communities in early New York, the early eighteenth century saw increasing entanglement between these communities.As an anthropological concept in the study of cross-cultural interaction, entanglement suggests a mutual social, political, or economic interdependence in which neither group fully controls the other, but does not necessarily imply a shared 'middle ground' space. For entanglement in historical and archaeological scholarship of Indigenous-settler interaction, see MacLeitch, Imperial Entanglements; Michael Dietler, "Consumption, Agency, and Cultural Entanglement: Theoretical Implications of a Mediterranean Colonial Encounter," in Studies in Culture Contact, ed. James Cusick, Center for Archaeological Investigations Occasional Paper 25 (Carbondale: Souther Illinois University, 1998), 288-315; Kurt Jordan, "Colonies, Colonialism and Cultural Entanglement: The Archeology of Postcolumbian Intercultural Relations," in International Handbook of Historical Archeology, ed. Teresita Majewskiand and David Gaimster (New York: Springer, 2009).full note Scholars have attributed some of the changes within Haudenosaunee communities during this period to increasing factionalism and fractures due to the increasing pressures of colonialism.Factionalism has long been the bugbear of academic Iroquois studies. For works that discuss factionalism as an explanation for eighteenth century internal divisions within the Confederacy, see William N. Fenton "Factionalism in American Indian Society" Actes du IV Congres International des Sciences Anthropologiques et Ethnologiques 2 (1955): 230-240; Richard Aquila, The Iroquois Restoration: Iroquois Diplomacy on the Colonial Frontier, 1701-1754. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 75-77; Richter, Ordeal, 6-7, 45-46, 116-117, 175-176, 200-206, 274-275, 307n34; Daniel K. Richter, "Iroquois versus Iroquois: Jesuit Missions and Christianity in Village Politics, 1642-1686," Ethnohistory 32, no. 1 (1985): 1-16, https://doi.org/10.2307/482090; Daniel Richter, "War and Culture: The Iroquois Experience." The William and Mary Quarterly 40, no. 4 (1983): 528-59. https://doi.org/10.2307/1921807; Robert F. Berkhofer, "Faith and Factionalism among the Senecas: Theory and Ethnohistory," Ethnohistory 12, no. 2 (1965): 99-112, https://doi.org/10.2307/480611; Gerald F. Reid, Kahnawà:ke: Factionalism, Traditionalism, and Nationalism in a Mohawk Community (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), xix-xxii and 6-7; Timothy Shannon, Iroquois Diplomacy on the Early American Frontier. (New York: Penguin, 2008), 55, 102, 200.full note

The Fort Hunter baptism register does show distinct internal divisions within the Haudenosaunee portion of the congregation, but these divisions were not the product of factionalism or colonial pressure.For discussions of the problems with emphasizing factionalism above all else, see Susan M Hill, The Clay We Are Made of: Haudenosaunee Land Tenure on the Grand River (Winnipeg. Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press, 2017); Alyssa Mt. Pleasant, "After the Whirlwind: Maintaining a Haudenosaunee Place at Buffalo Creek, 1780-1825" (PhD dissertation, Cornell University, 2007); Jon Parmenter, The Edge of the Woods: Iroquoia 1534-1701 (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2010); Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014); Margaret M. Bruchac, Savage Kin: Indigenous Informants and American Anthropologists, (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2018); Jon Parmenter, "'L'Arbre de Paix': Eighteenth-Century Franco-Iroquois Relations." French Colonial History 4 (2003): 63-80.full note The divisions within the Fort Hunter Anglican Mohawks were shaped by matrilineal clans, illustrating the ways in which Haudenosaunee families used Anglican godparentage to reinforce rather than replace Indigenous modes of affiliation and kinship recording.On clan affiliation and kinship networks in the Great Lakes, see Heidi Bohaker, "'Nindoodemag': The Significance of Algonquian Kinship Networks in the Eastern Great Lakes Region, 1600-1701," The William and Mary Quarterly 63, no. 1 (2006): 25-26, https://doi.org/10.2307/3491724\. On kinship and marriage as social organizer, see Juliana Barr, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 69; Anne F. Hyde, Empires, Nations, and Families: A History of the North American West, 1800-1860 (Lincoln, Neb., 2011), 33; Michael Witgen, An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America (University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 2012), 11; Raymond J. DeMallie, "Kinship: The Foundation for Native American Society," in Studying Native America: Problems and Prospects, ed. Russell Thornton (Madison, Wis., 1998), 306-56; Jay Miller, "Kinship, Family Kindreds, and Community," in A Companion to American Indian History, ed. Philip J. Deloria and Neal Salisbury (Malden, Mass., 2004), 139-53.full note The Fort Hunter register is a colonial document that recorded a colonializing perspective, but it offers a snapshot of the choices Haudenosaunee parents made to integrate—or not integrate—their settler neighbors through kinship connections. Digital analysis of these connections coupled with Indigenous studies methodologies—in this case, attention to Indigenous community knowledge and ways of conceptualizing identity and belongingLinda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2d ed. (London, 2012), 22, 39, 119; Lisa Brooks, "Awikhigawôgan Ta Pildowi Ôjmowôgan: Mapping a New History," The William and Mary Quarterly 75, no. 2 (May 3, 2018): 265 and 268; Alyssa Mt Pleasant, Caroline Wigginton, and Kelly Wisecup, "Materials and Methods in Native American and Indigenous Studies: Completing the Turn," The William and Mary Quarterly 75, no. 2 (May 3, 2018): 210.full note—offers new possibilities for understanding how Indigenous communities understood and directed entanglement with their settler neighbors.On the importance of critical race, ethnicity, and Indigenous studies in the digital humanities, see Lisa Brooks, "Awikhigawôgan Ta Pildowi Ôjmowôgan: Mapping a New History," The William and Mary Quarterly 75, no. 2 (May 3, 2018): 259-94; Roopika Risam, New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy (Evanston, Ill., 2019); Bessette, "W(h)ither DH?": 419-53; Lisa Spiro, "'This Is Why We Fight': Defining the Values of the Digital Humanities," in Debates in the Digital Humanities, ed. Matthew K. Gold (Minneapolis, 2012), http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/13; Moya Z. Bailey, "All the Digital Humanists Are White, All the Nerds Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave," Journal of Digital Humanities 1, no. 1 (Winter 2011), http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-1/all-the-digital-humanists-are-white-all-the-nerds-are-men-but-some-of-us-are-brave-by-moya-z-bailey/; Tara McPherson, "Why Are the Digital Humanities So White? Or Thinking the Histories of Race and Computation," in Debates in the Digital Humanities, ed. Matthew K. Gold (Minneapolis, 2012), 139-60; Jessica Marie Johnson, "Markup Bodies: Black [Life] Studies and Slavery [Death] Studies at the Digital Crossroads," Social Text 36, no. 4 (December 2018): 57-79; Jessica Marie Johnson, "Who's HiPS? Plain Sight Histories of Slavery," The William and Mary Quarterly 76, no. 1 (February 5, 2019): 15-18.full note

One of the main ways Haudenosaunee families shaped this engagement with the Anglican church and their settler neighbors was through women's godparentage connections. The Haudenosaunee congregation at Fort Hunter clustered according to clan affiliation, but women connected these clusters together. Indigenous women have long been acknowledged in the scholarly literature as intercultural connectors between Indigenous and settler groups via intermarriage between Indigenous women and settler men.Silvia Van Kirk, Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur Trade Society 1670-1870 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983); Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men; Susan Sleeper-Smith, "Women, Kin, and Catholicism: New Perspectives on the Fur Trade," Ethnohistory 47, no. 2 (Spring 2000): 423-52; Barr, Peace Came, 68-108; Jennifer M. Spear, Race, Sex, and Social Order in Early New Orleans (Baltimore, 2009), 40-41; Guillaume Aubert, "'The Blood of France': Race and Purity of Blood in the French Atlantic World," WMQ 61, no. 3 (July 2004): 439-78; Carl J. Ekberg, Stealing Indian Women: Native Slavery in the Illinois Country (Urbana, Ill., 2007), 27-28; Carl J. Ekberg and Anton J. Pregaldin, "Marie Rouensa-8cate8a and the Foundations of French Illinois," Illinois Historical Journal 84, no. 3 (Autumn 1991): 146-60; Richard White, The Middle Ground : Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815 (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), chap. 2 passim; Jennifer S. H. Brown, Strangers in Blood: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country (Norman, Okla., 1996)full note In the case of the Fort Hunter congregation, both Indigenous and settler women created connections within their own communities, but only a small handful of families created cross-cultural connections among Indigenous and settler godparents of Indigenous children. This created parallel congregations at Fort Hunter in which Haudenosaunee and settler congregants selected godparents from within their own ethnic communities with very littler cross-cultural godparentage.For similar patterns of parallel or separate but entangled Indigenous and settler communities, see DuVal, "Indian Intermarriage and Metissage in Colonial Louisiana": 291; Juliana Barr, "Geographies of Power: Mapping Indian Borders in the 'Borderlands' of the Early Southwest," The William and Mary Quarterly 68, no. 1 (2011): 18, https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.68.1.0005; Jacqueline Peterson, "Prelude to Red River: A Social Portrait of the Great Lakes Metis," Ethnohistory 25, no. 1 (Winter 1978): 49-51; Jacqueline Peterson, "Ethnogenesis: The Settlement and Growth of a 'New People' in the Great Lakes Region, 1702-1815," American Indian Culture and Research Journal 6, no. 2 (1982): 31-34; Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men, 30-32, 42-49full note

The ethnic and national boundaries within the Fort Hunter congregation are most visible in a modularity analysis of the network. Modularity identifies subcommunities within a network that have dense connections within the subcommunity and more sparse connections to the network outside the subcommunity.Because of the small size of this network, modularity was run in Gephi at resolution 2. Scott Weingart, "Networks Demystified 5: Communities, PageRank, and Sampling Caveats," the scottbot irregular, September 18, 2013, http://www.scottbot.net/HIAL/?p=39344; M. E. J. Newman, "Modularity and Community Structure in Networks," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, no. 23 (June 6, 2006): 8577-82, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0601602103; Robert Hanneman and Mark Riddle, Introduction to Social Network Methods (Riverside, Calif., 2005); Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler, Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives (New York, 2009). For overviews of social network methods in history, see Bonnie H. Erickson, "Social Networks and History: A Review Essay," Historical Methods 30, no. 3 (Summer 1997): 149-57; Charles Wetherell, "Historical Social Network Analysis," in New Methods for Social History, ed. Larry J. Griffin and Marcel van der Linden (Cambridge, [1999]); Susie Pak, Gentleman Bankers: The World of J. P. Morgan (Cambridge, MA, 2013)full note In the Fort Hunter network, modularity analysis detected three subcommunities in the Haudenosaunee portion of the network, four subcommunities in the settler portion, and one mixed Native-settler subcommunity that bridged the larger Haudenosaunee and settler portions of the network. The largest division within the congregation as a whole was between the Haudenosaunee and settler portions of the network, bridged by only Anna Peek, her husband, and adult children and their ties with a few Haudenosaunee families. Even within those two halves of the congregation, significant divisions of ethnicity and affinity existed.

| Subcommunity | Canasteje-Oseragighte | Kaghtereni-Uttijagaroondi | Kenderago-Canostens | Bridge | English | Dutch-English | Scots-Irish | Palatine | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals | 163 | 77 | 45 | 60 | 129 | 144 | 60 | 80 | 948 |

| Average degreeThe average degree for the large "giant component" of the network was also 5.9.full note | 5.9 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 6.1 | 5.9 |

In the settler portion of the congregation, the largest and densest subcommunity was comprised of intermarried English and Dutch congregants. In this subcommunity, individuals had a much higher average degree than individuals in other subcommunities, or in the network as a whole.The median degree for the entire network was 4. The Dutch subcommunity average was 7.3 and the median was 5.full note Degree measures the number of connections an individual has to others. In the case of the Fort Hunter network, degree indicates the number of others an individual was connected to by a baptism. A single baptism created and documented multiple network connections between the baptized child, its parents, the godparents and baptismal witnesses.On the practice of godparentage and baptismal sponsorship broadly in the early modern period, see Thomas S. Kidd and Barry Hankins, Baptists in America: A History (New York, 2015), 1-18; Travis Glasson, "Baptism doth not bestow Freedom: Missionary Anglicanism, Slavery, and the Yorke-Talbot Opinion, 170-1730." The William and Mary Quarterly. Vol 67, No 2 (April 2010), 279-318; E. Brooks Holifield, Theology in America: Christian Thought from the Age of the Puritans to the Civil War (New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University Press, 2005), 53-55; Stephanie Grauman Wolf, Urban Village: Population, Community and Family Structure in Germantown, Pennsylvania, 1683-1800 (Princeton, 1977): 293-294; Emily Clark and Virginia Meacham Gould, "The Feminine Face of Afro-Catholicism in New Orleans, 1727-1852," The William and Mary Quarterly 59, no. 2 (2002): 409-48, https://doi.org/10.2307/3491743; Rebecca Anne Goetz, The Baptism of Early Virginia: How Christianity Created Race (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012); Edward H. Tebbenhoff, "Tacit Rules and Hidden Family Structures: Naming Practices and Godparentage in Schenectady, New York 1680-1800," Journal of Social History 18, no. 4 (1985): 567-85; Jewel L. Spangler, Virginians Reborn: Anglican Monopoly, Evangelical Dissent, and the Rise of the Baptists in the Late Eighteenth Century (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008); Will Coster, Baptism and Spiritual Kinship in Early Modern England, St. Andrews Studies in Reformation History (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2002); Daniel Lindmark, "Baptism and Swedishness in Colonial America: Ethnic and Religious Membership in the Swedish Lutheran Congregations, 1713-1786," Scriptum 50 (2002): 7-31.full note For example, in early 1734 when William and Mary Sixbury presented their infant Cornelius for baptism, Cornelius was sponsored by John Hough and Mary Phillipse. Within the network, this single baptism created a maximally-dense cluster between the Sixburys and the two sponsors, meaning that each individual in the cluster was connected to every other individual. Later that same year, when William Sixbury and John and Susan Bowen sponsored the infant son of William and Cornelia Bowen, the adults reinforced natal ties between brothers John and William Bowen, ties across natal families between their wives, and ties of friendship or more distant relation with William Sixbury.Barclay Register, January 26, 1734/5, page [1] http://nyheritage.nnyln.org/digital/collection/p16124coll1/id/45261full note

Micro networks created by the baptisms of Cornelius Sixbury, January 1734/5, and Infant Bowen, September 1735

The density of connections within subcommunities of the Fort Hunter settler congregation reflected ethnic differences in the practice of baptismal sponsorship. As the most densely interconnected subcommunity at Fort Hunter, the Dutch subcommunity formed the heart of the settler congregation. Historically, Dutch families in New Netherland named very few baptismal sponsors or godparents, reflecting the relatively lower emphasis on godparents as spiritual educators in the Dutch Reformed Church.Tebbenhoff, 567-585; Simon Middleton, "Order and Authority in New Netherland: The 1653 Remonstrance and Early Settlement Politics," The William and Mary Quarterly 67, no. 1 (2010): 31-68, https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.67.1.31; Joyce D. Goodfriend, "The Historiography of the Dutch in Colonial America," in Eric Nooter and Patricia U. Bonomi, eds., Colonial Dutch Studies: An Interdisciplinary Approach (New York, 1988), 6-32full note By the 1730s, children in the Dutch subcommunity of the Fort Hunter congregation had as many as two godparents and four baptismal sponsors or witnesses, creating ties between as many as six adults at a time and contributing to the density of connections in this subcommunity. The Fort Hunter register suggests that as these Dutch families intermarried with newer English arrivals, English practices of godparentage became more prevalent. Even after the English takeover of New York, seventeenth century Dutch families had typically only named two sponsors, often the child's grandparents.Charles B. Moore, "English and Dutch Intermarriages," New York Genealogical and Biographical Record 4, no. 3 (July 1873): 127-39; Thomas Grier Evans, ed., Records of the Reformed Dutch Church in New Amsterdam and New York: Baptisms (1901), 1: 10-27.full note Dutch women in early New York typically remained members of the Dutch Reformed Church after marriage with English husbands.Goodfriend, 274-275.full note Many of the Dutch women at Fort Hunter, including Anna Peek, had their own children and had been themselves baptized in Dutch Reformed churches at Schenectady or Albany before relocating to Fort Hunter. The density of connections within the Dutch subcommunity at Fort Hunter and the prominence of intermarried Dutch women as bridges to other ethnic subcommunities within the settler congregation suggests that Dutch women used participation in Anglican baptism to solidify ethnic and religious ties even in the absence of a Dutch Reformed church.

The English subcommunity, which included William Johnson, his common law wife Catherine Weisenberg, and other British officers and their wives, had a lower density than the intermarried Dutch subcommunity.O'Toole, 45-47.full note The distinction between the Dutch and English subcommunities within this network is not a firm one and is much less stable than the distinctions between other subcommunities. At many modularities, the Dutch and English subcommunities were collapsed into one modularity class, and at other resolutions were fractured into several modularity classes. The other subcommunities discussed here were more firm in their boundaries across different resolutions. This indicates that Dutch and English settlers in New York had become thoroughly entangled and intermarried by the 1730s, yet maintained some ethnic distinction.

Part of this distinction came from their respective ties to British colonial infrastructure. The Dutch families at Fort Hunter had long-standing connections to the fur trade at Schenectady or Albany, but the English subcommunity was more closely connected to figures like Anna Peek who bridged the settler and Indigenous parts of the congregation. Many of the settlers in the English subcommunity had military or political ties to the British colonial infrastructure, either through formal commissions or through intermittent work as translators. This may represent a shift in the balance of power from the more trade-focused Dutch Commissioners of Indian Affairs at Albany towards the newer British military-diplomatic apparatus represented by more recent arrivals like William Johnson. As Johnson attempted to consolidate his political and economic power, he became ever more visible as the primary point of connection between settler and Indigenous leaders.On the tensions between Johnson and the Albany Commissioners, see Allen W. Trelease, Indian Affairs in Colonial New York: The Seventeenth Century (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 204-227; Hinderaker, The Two Hendricks, 50 and 67-69; MacLeitch, Imperial Entanglements, 37; David Armour, The Merchants of Albany, New York, 1686-1760 (New York: Garland, 1986), 66.full note As will be discussed further below, the prominence of Dutch and Haudenosaunee women as connectors between subcommunities suggests that multiple forms of connection between the Indigenous and settler congregants at Fort Hunter coexisted and overlapped even as men like Johnson attempted to consolidate diplomatic and political connections in their own control.

While the Dutch and English subcommunities were highly integrated and formed the center of the settler congregation, other European ethnic subcommunities at Fort Hunter were both more marginal and distinct within the congregation network. The density of connections within other subcommunities reflects the extent of their own integration with the Dutch and English subcommunities and their assimilation to Anglican baptismal practice. As German religious refugees left Europe in the early decades of the eighteenth century, the number of German Reformed and Lutheran churches in Pennsylvania and western New York doubled between 1730 and 1740.Patricia U. Bonomi and Peter R. Eisenstadt, "Church Adherence in the Eighteenth-Century British American Colonies," The William and Mary Quarterly 39, no. 2 (1982): 265, https://doi.org/10.2307/1918753; A. G. Roeber, "'The Origin of Whatever Is Not English Among Us': The Dutch-speaking and the German-speaking Peoples of Colonial British America," in Strangers within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British Empire, ed. Bernard Bailyn and Philip D. Morgan (Chapel Hill, 1991), 220-83; Aaron Spencer Fogleman, Hopeful Journeys: German Immigration, Settlement, and Political Culture in Colonial America, 1717-1775, 49558th edition (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996); Wolfgang Splitter, Pastors, People, Politics: German Lutherans in Pennsylvania, 1740-1790 (Trier Germany: Wissenschaftlicher, 1998); Stephen L. Longenecker, Piety and Tolerance: Pennsylvania German Religion, 1700-1850 (Metuchen, N.J: Scarecrow Press, 2000); Thomas J. Müller, Kirche zwischen zwei Welten: Die Obrigkeitsproblematik bei Heinrich Melchior Mühlenberg und die Kirchengründung der deutschen Lutheraner in Pennsylvania, 1st ed. (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1994); Aaron Spencer Fogleman, "Jesus Is Female: The Moravian Challenge in the German Communities of British North America," The William and Mary Quarterly 60, no. 2 (2003): 295-332, https://doi.org/10.2307/3491765.full note The growth and spread of these churches often could not keep up with the number of available and licensed ministers. During the 1730s, only one German Lutheran pastor, Wilhelm Cristoph Berkenmeier, ministered to the nearly two hundred miles between the Raritan Valley in New Jersey and the Mohawk Valley in New York, and Berkenmeier complained that his adult congregants forgot their religion and never gave their children instruction in the faith."Report by Pastor Wilhelm C. Berkenmeyer, Concerning the Meeting with the Lutheran Parish at Raritan, New Jersey, To Call a New Pastor, September 13, 1731," in John P. Dern, ed., The Albany Protocol: Wilhelm Christoph Berkenmeyer's Chronicle of Lutheran Affairs in New York Colony, 1731-1750, trans. Simon Hart and Sibrandian Geertrud Hart-Runeman (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1971), xxiv, 14-15, and 88.full note Outside the counties surrounding New York City, New York did not require tax support of churches, and congregants attended—or did not attend—whichever church they chose.John B. Frantz, "The Awakening of Religion among the German Settlers in the Middle Colonies," The William and Mary Quarterly 33, no. 2 (1976), https://doi.org/10.2307/1922165, 273.full note European settlers in New York often therefore felt a "protestant responsibility" to offer and accept baptism from other denominations when their own ministers were distant or rarely visited far-flung communities.Lindmark, 7-31. On the diversity and divisions in specifically German religious practice in early America, see Sidney E. Mead, "Denominationalism: The Shape of Protestantism in America," Church History, XXIII (1954), 29I-320, and Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (New Haven, Conn., 1972), 230-23I, 472-475; Frantz, 266-288.full note Dutch Reformed, German Reformed, Lutheran, and Presbyterian settlers like those near Fort Hunter practiced a capacious sacrament, with rites performed by a Protestant minister of another denomination viewed as an acceptable alternative if one of the preferred denomination was not available.Bonomi and Eisenstadt, "Church Adherence," 251; Frantz, 266-288.full note At Fort Hunter, Barclay administered baptism to children of Europeans in the area who did not necessarily consider themselves Anglican even if they attended service and had their children baptized at Fort Hunter.

Palatine settlers especially guarded their religious separatism from the Church of England even during their refuge in England before emigration to New York, and married primarily among themselves into the nineteenth century.Otterness, 145; Roeber, 14.full note The Palatine subcommunity at Fort Hunter had a much lower degree of internal connection than the other settler subcommunities. This reflected both their own baptismal practices of having only a few baptismal sponsors, and their separatism from the larger Dutch and English settler congregation. Despite the capacious Protestant sacrament necessitated by far-flung settlement, Palatine communities in early New York resisted Anglican efforts to incorporate them. Eighteenth century New York governors increasingly sought to privilege the Church of England as the primary church of the colony, and attempted to end the seventeenth-century practice of allowing tax support for other denominational churches.Katherine Carté Engel, "Connecting Protestants in Britain's Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Empire," The William and Mary Quarterly 75, no. 1 (February 6, 2018): 47; Richard W. Pointer, Protestant Pluralism and the New York Experience: A Study of Eighteenth-Century Religious Diversity (Bloomington, Ind., 1988), 53-55; Evan Haefeli, New Netherland and the Dutch Origins of American Religious Liberty (Philadelphia, 2012), 257-61.full note Colonial officials hoped for a shared Protestant faith to unite Britain's many fractious subjects.Engel, 51; Goodfriend, "Social Dimension of Life," 261-262; John B. Frantz, "The Awakening of Religion among the German Settlers in the Middle Colonies," The William and Mary Quarterly 33, no. 2 (1976): 266-88, https://doi.org/10.2307/1922165; W. R. Ward, The Protestant Evangelical Awakening (Cambridge, 1992), 103-7; Daniel L. Brunner, Halle Pietists in England: Anthony William Boehm and the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (Göttingen, Ger., 1993), 58; Renate Wilson, "Halle Pietism in Colonial Georgia," Lutheran Quarterly 12, no. 3 (Autumn 1998): 271-301; Sugiko Nishikawa, "The SPCK in Defence of Protestant Minorities in Early Eighteenth-Century Europe," Journal of Ecclesiastical History 56, no. 4 (October 2005): 730-48.full note The notable separatism of both the Palatine and Scots-Irish subcommunities within the Fort Hunter network suggests that this shared Protestant faith did not notably unify the many European ethnic groups in Britain's colonies.

The Scots-Irish subcommunity had even fewer connections to the larger settler network. The baptismal sponsorship practices of the Scots-Irish subcommunity, with several sponsors and witnesses per baptism, aligned more closely with the Dutch subcommunity. Despite this, only a few individuals connected the Scots-Irish community to the wider network, creating a dense and insular subcommunity.On Scotch-Irish PA ethnic solidarity, see Patrick Griffin, "The People with No Name: Ulster's Migrants and Identity Formation in Eighteenth-Century Pennsylvania," William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 58, no. 3 (July 2001): 587-614; Gregory H. Nobles, "Breaking into the Backcountry: New Approaches to the Early American Frontier, 1750-1800," The William and Mary Quarterly 46, no. 4 (1989): 642-70, https://doi.org/10.2307/1922778; Warren R. Hofstra, "'The Extention of His Majesties Dominions': The Virginia Backcountry and the Reconfiguration of Imperial Frontiers," The Journal of American History 84, no. 4 (1998): 1281-1312, https://doi.org/10.2307/2568082; James G. Leyburn, The Scotch-Irish: A Social History (University of North Carolina Press, 1989); Russell M. Reid, "Church Membership, Consanguineous Marriage, and Migration in a Scotch-Irish Frontier Population," Journal of Family History 13, no. 4 (October 1, 1988): 397-414, https://doi.org/10.1177/036319908801300403.full note The most prominent connector to the English subnetwork was William Corry, a business associate and political ally of William Johnson. Corry viewed himself as a local leader, and promised Johnson in 1751 that he had "directed my people to vote on your side" in a local election.William Corry to William Johnson, December 31 171, SWJP 1:358-359; see also Allan Tully, Forming American Politics: Ideals, Interests, and Institutions in Colonial America, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2019).full note Corry acquired this influence with "his people" through a combination of kinship and patronage. In 1737, the twenty-seven year old, recently immigrated Corry unsuccessfully petitioned the colony for a grant of 100,000 acres in the Mohawk Valley. He intended to settle a number of other families from his home country of Ireland on this grant. Corry would later successfully acquire a grant in the Mohawk Valley, and parlayed part of this grant into political influence by conveying it to the Lieutenant Governor of New York in a transaction that was contested into the nineteenth century.Gustavus Myers, History of the Supreme Court of the United States. (New York: C.H. Kerr, 1912), 36-37; for the nineteenth century contestation of the grant, see Charles W. McCurdy, The Anti-Rent Era in New York Law and Politics, 1839-1865 (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2003), 303. See also "A Map of a Tract of Land granted to William Corry and others," 19 November 1736, Cockburn Family Papers 1732-1864 SC7004 Box 4 folder 17, New York State Library; "Copy of a Field Book of a certain tract of land granted to William Corry and others bearing date the 19th of December 1737," Cockburn Family Papers 1732-1864 SC7004 Box 4 folder 18, New York State Library.full note The baptisms of Corry's four children Ann, Alice, Charles, and Moses formed ties between Corry and his wife Elizabeth, the prominent Dutch landholding Wemps, and the more recently immigrated Scots-Irish Welch and Mills families. William Corry's business and political ambitions gave him a number of connections that made him unique in the Fort Hunter congregation and the Scots-Irish subcommunity, but he was exceptional in another way as well: he was the only man who connected the Scotch-Irish subcommunity to other groups.

The other two individuals who connected the Scotch-Irish subcommunity to the Dutch and English subcommunities were both women: Mary Linch and Mary Quackenbus. Linch and her husband Hugh do not seem to appear in other records. Quackenbus and her husband Abraham were part of the extensive and notable Quackenbus family, but Abraham was not among the more copiously documented and financially successful Quackenbuses. Mary Linch and Mary Quackenbus anchored the Scotch-Irish subcommunity to the English and Dutch subcommunities. William Corry attained his prominence because of his money, land, and political influence, but these two relatively undocumented women functioned similarly as bridges despite their respective marriages to unnoteworthy men. Like many settler women in early New York, Linch and Quackenbus directed their families' religious life.Goodfriend, 274-275; Patricia U. Bonomi, Under the Cope of Heaven. Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America (New York, 1986), 105-115; Mary Maples Dunn, "Saints and Sisters: Congregational and Quaker Women in the Early Colonial Period," in Janet Wilson James, ed., Women in American Religion (Philadelphia, 1980), 27-46; Joan R. Gundersen and Gwen Victor Gampel, "Married Women's Legal Status in Eighteenth-Century New York and Virginia," WMQ, 39 (1982), 114-134; Sherry Penney and Roberta Willenkin. "Dutch Women in Colonial Albany: Liberation and Retreat." de Halve Maen, LII (Spring1977) 9-10, 14-15.full note This included participating in baptisms more frequently than their husbands, and at Fort Hunter this social fabric made visible the boundaries and connections between disparate settler communities.

The enslaved African community, though comparatively very small in relation to the rest of the network, offers an important counterpoint to the connections among the rest of the congregants. Two of the three enslaved natal families, the Powels and the Specks, shared dense connections to one another.The Specks remained prominent members of the Albany-area free and enslaved African American community into the present. A project in progress headed by Ian Mumpton at Schuyler Mansion Museum, Albany NY, traces the family's roles as baptismal sponsors of other free and enslaved blacks through the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. On the place of baptism in creating and maintaining ties between enslaved people throughout early America, see Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York, 1974), 133-142; Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South (New York, 1978), chap 3 passim; Walter Hawthorne, From Africa to Brazil: Culture, Identity, and an Atlantic Slave Trade, 1600-1830 (Cambridge, 2010); Spear, Race, Sex and Social Order; Glasson, "'Baptism Doth Not Bestow Freedom'"; Clark and Gould, "The Feminine Face of Afro-Catholicism in New Orleans,"full note Unlike the Native portion of the congregation, which shared very dense connections between Native people and relatively sparse connections with the settler portion of the congregation, all enslaved people in the Fort Hunter congregation had ties with both enslaved African and white baptismal sponsors. The enslaved Africans in the Fort Hunter congregation were thoroughly enmeshed in the white settler network despite dense ties between one another, whereas the Haudenosaunee community shared kinship ties with the white community only along its borders. Haudenosaunee communities did have contact with and occasionally adopted African individuals in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but those ties were made within the context of Haudenosaunee practices rather than Anglican baptism.Hart, "For the Good of Our Souls"; William Bryan Hart, "Black 'Go-Betweens' and the Mutability of 'Race,' Status, and Identity on New York's Pre-Revolutionary Frontier," in Contact Points: American Frontiers from the Mohawk Valley to the Mississippi, 1750-1830, ed. Fredrika J. Teute and Andrew R. L. Cayton (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 88-113; Matthew Dennis, Cultivating a Landscape of Peace: Iroquois-European Encounters in Seventeenth-Century America (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1993). full note

The gendered connections between Africans and white sponsors at Fort Hunter underlines the importance of property ownership in sponsoring enslaved children, themselves property. Within the framework of Anglican baptism, an enslaved child and family's documentable ties were centered on the white household in which they were enslaved. White men were the main sponsors for enslaved children, both within their own households and in others' households. John Wemp, one of five men originally awarded the contract to build Fort Hunter in 1711,"Contract to Build Forts in the Mohawks and Onondaga Countries," October 11, 1711. E. B. O'Callaghan, Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York (Albany: Weed, Parsons, Printers, 1853), 5:279-281.full note was a sponsor for two white children and five enslaved black children. Wemp removed from Schenectady to the Fort Hunter area by late 1733, and by 1737 owned several thousand acres of land in the area.August 5 and 13, 1737, 12:224; September 23, 1737, 12:225; November 22, 1737, 12:226; October 29, 12:231; November 4, 1737, 12:231; November 11 and 12, 1737, 12:231; December 16, 1737, 12:232 Calendar of NY Colonial Manuscripts Indorsed Land Papers In the Office of the Secretary of State of New York, 1643-1803. Albany: Weed, Parsons & Co, 1864.full note Wemp owned all five of the enslaved children whose baptisms he witnessed, as well as their parents. Baby Mary was born to Primus and Rachel Speck in 1743, and when Wemp drew up his will four years later, the little girl and her father, along with eight other enslaved people, were bequeathed separately to various Wemp relatives, including Wemp's son Isaac, who himself sponsored the baptism of another enslaved child.Mary, 1743, Barclay Register; "Will of Johannes Myndert Wemple, March 5, 1747/8," in The Wemple Family by William C. Wemple. Cleveland, OH: 1939.full note Wemp's will did not include Primus and Rachel's other four children.

Very few white women sponsored enslaved children, and those who did so were prominent property owners themselves. Only two white women, Mary Phillipse and Anna Peek, stood as godparents to enslaved children. Both sponsored baptisms for enslaved children outside of their own households. Their prominence as property owners at Fort Hunter suggests that baptism and education of enslaved children was viewed as part of wealthy white women's responsibilities within and beyond their households.Clark and Gould, 409-448; Susanah Shaw Romney, "Intimate Networks and Children's Survival in New Netherland in the Seventeenth Century," Early American Studies 7, no. 2 (2009): 270-308; Sue Peabody, "Madeleine's Children: Slaves from Isle Bourbon (Present-Day Réunion), Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries," Clio. Women, Gender, History, no. 45 (2017): 166-78; John M. Monteiro, "From Indian to Slave: Forced Native Labour and Colonial Society in São Paulo during the Seventeenth Century," Slavery & Abolition 9, no. 2 (September 1, 1988): 105-27, https://doi.org/10.1080/01440398808574952; David M. Stark, "Ties That Bind: Baptismal Sponsorship of Slaves in Eighteenth-Century Puerto Rico," Slavery & Abolition 36, no. 1 (January 2, 2015): 84-110, https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039X.2014.935127.full note Mary Phillipse was among the wealthiest landowners in the Mohawk Valley.William Pelletreau, History of Putnam County, New York, (W.W. Preston & Company, Philadelphia, 1886); Historical and Genealogical Record Dutchess and Putnam Counties New York, (A. V. Haight Co., Poughkeepsie, New York, 1912), 62-79; F.O. Morris, "Philipse of Philipsburgh," in The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, vol. 10 (1856)full note As the widow of William Phillipse, youngest brother of the wealthy bachelor proprietor Adolph Phillipse of the large Philipse Patent, she was not as extraordinarily wealthy as her brother-in-law, but held significant property after her husband's death. She was among a small handful of white women who appeared on a Fort Hunter area tax list in the late 1760s, one of the more heavily taxed property holders assessed at seventeen pounds and five day's public work--likely done by enslaved people.Jeptha Simms, History of Schoharie County and Border Wars of New York. (Albany, NY: Munsell and Tanner, 1845): 150.full note When baby Mary was born to Primus and Rachel Speck in 1743, her baptism solidified ties between her three white sponsors and the three main branches of settler power in the Mohawk Valley: John Wemp, the large landowner; Mary Phillipse, the relative of a wealthy proprietor; and William Prentop Jr, a prominent translator in negotiations with the Mohawk. Enslaved children's baptisms formalized not only their parents' religious choices, or their enslavers' assertion of religious and domestic control, but also created an opportunity for whites to solidify political and economic ties through the enactment of fictive kinship to an enslaved child.

The network of connections between the Wemp and Speck families offer a stark illustration of the social and legal erasure of enslaved people's ties outside the household in which they were enslaved. The most-connected enslaved African individuals were both women, Rachel Speck and Elizabeth Powel, but their primary connections were with prominent white men. Speck and Powel lacked documented direct connections with one another in this network, although members of their families sponsored one anothers' children. The indirect connections between these two prominent enslaved African women suggests that the enslaved Specks and Powels shared relationships that may not have been visible to Barclay and other white authorities. Enslaved women were in many ways invisible in early America, and their sketchy presence in the Fort Hunter congregation is typical of the documentary erasure of enslaved people generally and enslaved women specifically.Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive, Reprint edition (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).full note Although all the enslaved people in the Fort Hunter network were thoroughly and densely enmeshed in the surrounding white network, the frequency of their indirect connections to one another suggests a sort of secondary shadow network connected enslaved people, one that was not visible or was simply not documented by white authorities.For this archival and network absence of enslaved people in another kind of network, see Klein, "The Image of Absence."full note

Anna Peek held much less property than Philipse and property of a different kind, positioning her differently within the social fabric of the Fort Hunter congregation. Like Philipse, Peek used the baptism of enslaved children to create and maintain social ties to prominent white men in the Mohawk Valley. Anna and her husband Joseph Clement witnessed the baptism of the enslaved Primus and Rachel Speck's son Joseph, alongside slaver owner John Wemp, descendant of one of the wealthiest settler landholding families in the Schectady-Albany area.Joseph, 1735, Barclay, "Register of Baptisms."; Hudson-Mohawk Genealogical and Family Memoirs, edited by Cuyler Reynolds (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1911), 1663. On Myndert Wemp's political loyalties and somewhat perplexing Leislerian ties considering his father Jan Barentsen Wemp's proprietorship, see Thomas E Burke, Mohawk Frontier: The Dutch Community of Schenectady New York 1661-1710 (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2009), 165. On the extended Wemp family's wealth and influence in the region, see Janny Venema, Deacons' Accounts, 1652-1674, First Dutch Reformed Church of Beverwyck/Albany, New York (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1998), 4-5; Albany County (N.Y.), Early Records of the City and County of Albany, and Colony of Rensselaerswyck (University of the state of New York, 1918) 63-64, 72-73, 106-107, 265, 283 and 285; Arthur James Weise, Troy's One Hundred Years, 1789-1889 (W.H. Young, 1891), 11-16.full note Clement and Peek also shared godparentage ties with William Johnson when they all witnessed the baptism of Joseph, the son of Johnson's slaves Powel and Elizabeth. Like the baptism of the younger enslaved Joseph, this second baptism cemented an important social and economic tie between the newly-arrived and ambitious William Johnson and the more established Anna Peek and Joseph Clement.

Unlike Mary Philipse, the source of Peek's relative wealth also brought her into daily contact with Haudenosaunee people whose children's baptisms she also witnessed, and it was these ties William Johnson likely sought to leverage with the baptism of the enslaved infant Joseph. Peek operated a tavern with her husband that served both the Mohawk and settler communities near Fort Hunter, and from this tavern traded cloth and other fur trade goods with their Indigenous customers. Joseph Clement and Anna Peek both had longstanding ties to the Mohawk Valley region and more recent ties to the fur trade. Peek's widowed grandmother was among the first Dutch settlers at Schenectady and Peek's father opposed Leisler's Rebellion in the late seventeenth century.Thomas Burke, "Leisler's Rebellion at Schenectady, New York, 1689-1710," New York History 70, no. 4 (October 1989): 405-30; Burke, Mohawk Frontier, 177-179; NYCD 4:939-941; Jonathan Pearson, A History of The Schenectady Patent in the Dutch and English Times. Edited by J.W. MacMurray. (Albany: Joel Munsell's Sons, 1883), 82-230; John Sanders, Centennial Address Relating to the Early History of Schenectady, and Its First Settlers: Delivered at Schenectady, July 4th, 1876 (Van Benthuysen Printing House, 1879), 83-84.full note Anna's many sisters also married into prominent founding Schenectady anti-Leislarian families.For the marriages of Anna's sisters and nieces, see Jonathan Pearson, Contributions for the Genealogies of the Descendants of the First Settlers of the Patent and City of Schenectady, from 1662 to 1800 (J. Munsell, 1873), 8, 37, 140, 160, and 206; and Sanders, Centennial Address, 71, 82, 105, 142, 161, and 167.full note When Leisler attempted to take control of the colony in 1689, anti-Leislerian anglophone settlers at Schenectady and Albany courted Mohawk support against Leisler by offering their own support against the French then making military raids against western Haudenosaunee nations.Richter, Ordeal, 164-166; Kees-Jan Waterman, "We Must Stick To Brother Quider": Reverberations Of Leisler's Rebellion And Its Aftermath Among The League Iroquois, 1688-1693." De Halve Maen 67, no. 1 (Winter 1994): 21-27; Thomas J. Robertson, "Then Wee Were Called Brethren": The Iroquois And Leisler's Rebellion, 1689." De Halve Maen 68, no. 3 (Summer 1995): 54-64; Andrew T. Stahlhut, "'Great Security ... from the Insults of Our Enemies': Provincial Unity during the Era of Leislerian Factionalism in New York, 1691-1709." De Halve Maen 80, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 47-56.full note Part of this courtship included Dutch Reformed minister Godfridus Dellius' baptism and political overtures to several young Mohawks who maintained close diplomatic ties with Albany over the following decades.Richter, Ordeal, 165; Lois M. Feister, "Indian-Dutch Relations in the Upper Hudson Valley: A Study of Baptism Records in the Dutch Reformed Church, Albany, New York," Man in the Northeast, 24 (Fall 1982), 89-113; DRCHNY 3: 799, 814-818; 4:47-48, 77-78; and 92-93.full note Although these baptized Mohawk men and their families are not visible in the Fort Hunter baptisms, the prominence of anti-Leislerian settler families as the main connection between the settler and Indigenous portion of the congregation suggests the importance of generational ties in shaping cross-cultural contact in early New York.

Joseph Clement likewise had anti-Leislerian family ties, as well as more recent fur trade connections. Clement's parents Jan and Maria arrived in New Netherland as children just before the 1664 English takeover, and Joseph's English, anti-Leislerian stepfather Benjamin Roberts bought land along the Mohawk River just after arriving in 1669.Pearson, A History of The Schenectady Patent, 210; William Max Reid, The Mohawk Valley: Its Legends and Its History (G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1904), 53-57; George Rogers Howell, History of the County of Schenectady (W. W. Munsell & Company, 1886), 2, 15, 17; Burke, Mohawk Frontier, 193.full note After Clement and Peek married in 1710, Clement was a carpenter and interpreter at the British trade outpost of Oswego from 1727 to 1733, when they bought a lot along the Mohawk River.Nancy Hagedorn, "Brokers of Understanding: Interpreters as Agents of Cultural Exchange in Colonial New York," New York History 76, no. 4 (1995): 379-408, 226; Maryly B Penrose, Compendium of Early Mohawk Valley Families (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc, 1990)full note When Johnson arrived in New York in 1738, he settled nearby and made part of his fortune supplying Oswego after 1739. Like the baptism of the enslaved Joseph, Johnson also had his children by his common-law wife Catherine Wysenbergh baptised at Fort Hunter with Peek and Clement as witnesses, though Johnson himself was not registered as the childrens' father in the baptism register. As a newly arrived trader with larger ambitions, Johnson likely sought to leverage the baptisms of his own children and the children of people he enslaved into valuable connections with more established traders like Peek and Clement.

Johnson's attempts to parlay these social connections to his own economic benefit soon soured his relations with his more established neighbors. As more experienced traders, Peek and Clement sold a range of goods from their tavern and served alcohol to both settler and Indigenous customers, a practice which was intermittently illegal in the early eighteenth century without a license. As early as 1720, almost twenty years before Johnson arrived in New York, Mohawk chief Hendrick accused Joseph Clement and three others of selling rum to Indians "so plentifully as if it were water out of a fountain."3 September 1720 "Att a Meeting of the President Collo Peter Schuyler Esqr and the Commissioners of the Indian Affairs." DRCHNY 5:569; see also Preston, 89.full note Johnson, who later became one of Hendrick's close allies, leveled the same accusation against Clement and Peek throughout the 1740s and 1750s. This illicit liquor trade, along with their more legal trade in cloth and other goods at their tavern, brought the Clements into daily contact with both their settler and Indigenous neighbors. Their eldest son Jacobus was born around the time the Clements began selling rum and seventeen when they stood as godparents for a Native child for the first time.Records of the Reformed Dutch Church of Albany, New York. (Albany NY: Holland Society of New York, 1904-1905), 3:12, 114, 123; 4:6, 21, 44, 45, 53, 67, 98.full note Jacobus went on to become a trader in his own right and interpreter who worked alongside Johnson, suggesting that his family's connections with the Native population were sustained over a long period.DRCHNY, 7:96; SWJP, 1:625-36; 9:466, 489-90, 518, 926-40, 952-57full note